Portrait by Randy Martinez

New York Times Columnist of "Your Money"

Author, The Opposite of Spoiled

It’s a very difficult thing to acknowledge our own privilege. It’s something that as parents we need to do before we can begin to explain it to our kids.

Interview by Heidi Legg

"If I'm really honest with myself, the majority of the people who are going to read this book can afford really nice vacations, they can afford the iPhone for the kid, they can afford to buy a new car for the kid, they can afford much better than average clothes but the question is: should they?" – Ron Lieber

Ron Lieber is the “Your Money” columnist for The New York Times and his new book "The Opposite of Spoiled" is meant to be a guide for parents on how to teach kids about money and values. I sat down with Ron in New York on the recommendation of Mark Stanek, the head of school at Shady Hill School in Cambridge – long known as one of the most progressive schools in America and as "The Outdoor School.”

As we look around the world and discuss income disparity and economic diversity, we see that these subjects remain extremely uncomfortable to discuss. Even in the Republic of Cambridge, where some kids go to school with no lunch and others live in 5 to 10 million dollar houses and have grown up on Whole Foods, we have a hard time talking about it. I’m having a hard time even writing this intro! And you know what? It seems more difficult to talk about it when incomes are even closer to one another. Those might be the hardest places to have the conversation, but Ron Lieber believes it is time. I suppose in posting this interview, so do I. So let’s get uncomfortable.

Do you have kids?

I have a daughter who is eight years old and is in the third grade.

Do you consider yourself wealthy?

Yes.

How do you define wealth?

I define wealth as having everything I need and everything we need because we're a family unit, and most of what we want.

What motivated you to write this book?

My daughter was asking questions about what we had and why we didn't have what other people had and the questions stopped me in my tracks. I'm supposed to be the person who has all the answers about money for a living, but when it comes to parenting, none of us have all the answers. I realized that these questions she was asking me inspired this potent mix of both thinking through the numbers but also experiencing intense feelings.

In writing about money for a living, I'm always looking for the topics that have kind of an emotional pull. Money and investing can be very dry, but the people who are most successful with handling money in their own lives, no matter how much they have, are the ones who are in tune with their emotions and in tune with the things that are driving their behavior.

I recognized an emotional response in myself and I began thinking that I'm probably not the only one who has this response when my kid ask a question that sort of sounds like an accusation, and where I've been found wanting in the provider category.

I did some blog posts over the course of a year where I tried to answer some of the toughest questions kids had about money. As a result, people in the community began thinking, ‘this is the guy who can come to our school and help set all the parents straight around questions such as: who has more, who has less, and how that came to be and whether it's fair.’ When I received invitations to go speak, I knew right away that it was an incredible opportunity to get people talking about money much more often and in a different way.

Is your daughter in public or private school?

She's in private school.

Were these invitations from public or private schools?

These happen to be private schools but I also talk to public schools, different community organizations, and religious groups. It's not just the people who have more money than average who are interested in talking to their kids more constructively about money. I think that desire exists across the socioeconomic strata.

Did your research make you uncomfortable at times?

Sure. I think the hardest chapter to write in the book was the chapter about how we do and don't talk about social class and what we're willing to admit to ourselves, and to one another, about just how good we have it.

When you asked me whether I consider myself wealthy, it took a lot of work personally to get to the point where I could say I was, without worrying that it would be somehow misconstrued because people imbue that word with all sorts of meaning. To me, it means something different than I think it means to a lot of people. But that aside, you asked what made me uncomfortable.

What am I most worried that someone could misinterpret or take the wrong way? I was very careful with the tone in that chapter [about how we do and don’t talk about social class], but I also felt like people needed to be taken by the shoulders a little bit and say, 'hey, your definition of 'middle class' is probably not very close to the actual definition of middle class.' It's perfectly understandable. This is not a character flaw that any of us have. It just so happens that most of the time most of us tend to surround ourselves with people who are more or less like us.

Not everybody does this but a lot of people do because that's what's most comfortable. I'm speaking purely in socioeconomic terms right now, because race is a whole other thing.

If you're hanging out with somebody, what tends to be most comfortable is not running around in a social group of people who have a lot more money than you because then you can't afford to do the things that they do. And if you're hanging out with a lot of people who have way less than you, then it can be uncomfortable for them, and you don't want to be rubbing their nose in it since there are things that you can do that they can't do. It's uncomfortable. We tend to gravitate towards people who are more or less like ourselves and when we do that, there are often people who are close to us who have a little more and people who are close to use who have a little less. As a result, we say, 'oh, we're in the middle. We must be middle class.'

It’s a very difficult thing to acknowledge our own privilege. It’s something that as parents we need to do before we can begin to explain it to our kids, because I think the conversation for most readers of hard cover nonfiction – which is itself a luxury product – are people with disposable income. If you have disposable income, you're firmly into the sort of top third of income and social class in American. You are privileged.

Did you unearth any guiding ideas about the new stratospherically wealthy class that has emerged in the past decade?

We've been talking so far about the grownups getting their heads together around this topic, but one of the things that's really hard for kids is that there's so much more access than there used to be, even five or ten years ago, to what everybody else has and what they're doing with it and where they're doing it and who they're with when they’re doing it. It’s both people that they don't know, who they follow on Twitter or Instagram or watch on reality television, but it's also people that they do know.

What kids fail to recognize – and I think even grownups fail to recognize a lot of the time – is that social media is really where it starts to have the potential to be destructive.

On social media, everybody is presenting the very best version of themselves. It's a literal teenage highlight reel for the kids who use it, and use it frequently, and it's almost like a sales presentation. 'This is me and my great life. It's the best version of myself.'

I think a lot of grownups experience this on Facebook too. I find the experience of reading Facebook to be a little uncomfortable sometimes. It's not that I never make personal posts, but I would never want anything that I post to be the cause of somebody else's envy.

You use if for your work, columns and your book and I use it for these interviews. Isn't that self promotion?

I answer a lot of queries from people who need help with random things. It's one of my main forms of procrastination. But as far as the kids go, they get a confused sense of how the world works and what everybody else's life is like and it's very easy for them to find their own life somewhat diminished by comparison if they don't come to grips early on with the way in which their peers are using social media.

I can't tell you the number of times I heard in the last couple years, this is a Manhattan issue. But it's probably an issue in your community too, parents who say, 'if I see one more private jet on my kid's Instagram feed, I'm going to crack their phone in half.' There's literally an Instagram account called Rich Kids Of Instagram, which is particularly obnoxious, but if your kids go to private school or you live in an upper middle class or above suburb, there's going to be somebody who's getting to do something stratospheric.

What do you say to these parents?

The solution is that you have to treat social media the same way you treat regular media and in the same way you are presumably thinking pretty hard about what your kids get to watch on TV: you also should be looking over their shoulders and having their usernames and passwords to see what they're looking at on social media. You should be talking about it and reminding them that this is not the real world. These are people who are trying to impress one another. You may think that this is what your life should be like, but this is in fact an exaggerated version of everybody else's life and you don't see the mundane stuff and the struggles here.

Is all this privilege even healthy for kids? Is there a point when we ask parents who can afford the stratosphere to cut back on what they buy for their kids?

This was a struggle in how much I wanted to dive into the world of the one percent in this book. I was trying to write a much more broad based book. There's a lot of really good research out there on just how many problems, not just affluence, but materialism in particular can cause. For people who are interested in reading about that, Madeline Levine's book The Price Of Privilege is sort of the parenting bible on that front and the best book I've ever read about the problematic impact of materialism.

Look, whether you have a huge net worth or whether you're on the lower end of upper middle class, the fact is that you can afford all the things that your kids need and most of the things that they want. But you also know that it's not good to give them or let them have most of the things that they want, and that’s the thing that is most complicated for parents in this context.

This is where you set up what are ultimately completely artificial limits on what they can do, what they can have, and how much of it. This gets complicated both in terms of what you're willing to pay for yourself, but also what you let them pay for with the money that they get in allowance or with the money they earn on their own because you're still responsible for them, at least until they're eighteen. You get to decide, at least in theory, how they’re spending their money.

The complicated question is when and how do you set those limits? And it's different in all different categories. There's the 'what sort of vacations do we take as a family?' question which is really a family choice that has as much impact on them as it does on you. There's the 'when do they get a phone and what kind of phone do they get?' There's the 'should they have a car and, if so, what kind?' There's the 'what sorts of clothing are we going to buy them and how much of it?' There's the whole athletic team travel bucket, which has become an explosive suck on time and money. The decision tree and discussion points are different for all of those.

Yes, the whole athletics thing is turning out to be more than a bit crazy… And it’s all driven to fill college applications, with is another machine.

There is a central question of human existence that I find applies in this context really well: how much is enough? It’s not a rhetorical question, and one of the hardest things about parenting in this context is actually coming up with an answer in each and every category and being able to articulate it to kids, because they deserve to know the reason.

Such as who can afford $1,000 for hockey? Everyone should be able to play hockey!

But this is not Canada. There are not a lot of hockey rinks. Ice time is expensive and you can't play outdoors on ponds for the most part.

You can in a lot of states.

Minnesota. You're in an urban or semi-urban environment. There's a cost.

How do we give children an answer in each of these categories?

I think they deserve an answer. In fact, I think they're entitled to one. And parents don't like hearing that because it means that they have to first articulate it to themselves, and then to their kids: ‘why it is that some things are more important than others?’ Inevitably you're not going to check the most expensive box for all of these categories and your kids are also going to be looking to you to see what you do in your own life: how much you're spending on your athletic pursuits, what kind of car you drive, how much you spend on vacation, etc…

What are some of the best questions you’ve been asked on this subject?

One time somebody raised their hand and said, 'my son came to me the other day and he asked, 'why won't you let me have a carnivorous plant terrarium if my sister can wear Hunter boots?'' and I thought that was so awful on so many levels. You break those two things down in a variety of ways and what we've got here is a kid who's confusing two different categories of spending because, to me, a carnivorous plant terrarium is a tool for learning whereas Hunter boots are items of clothing.

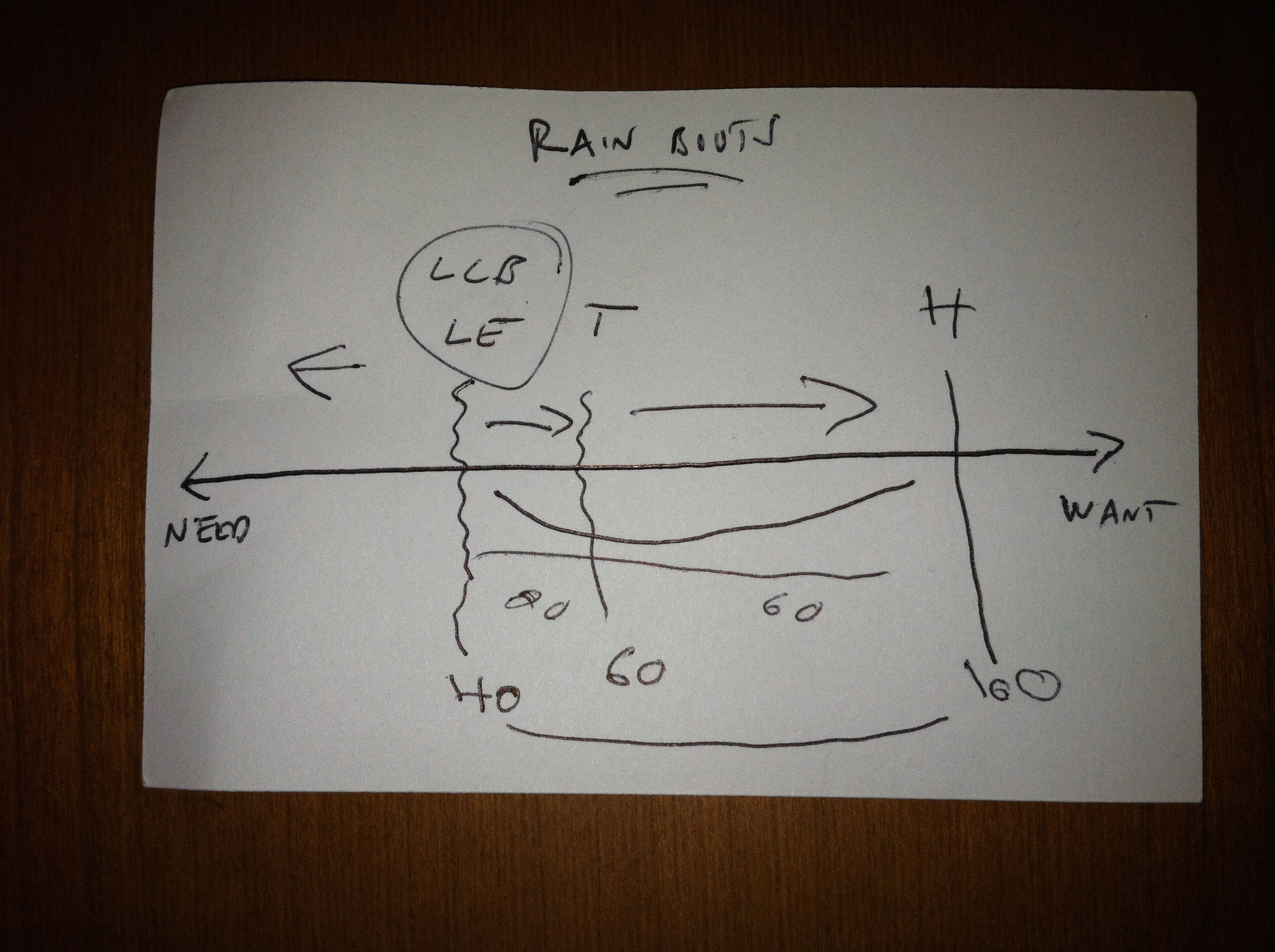

So let’s break this down: I have this sort of tool I use for these kinds of scenarios, which I call 'the want/need continuum.' If we're in the rain boots category, we say every kid needs rain boots if you're in a place where it rains. I draw up a horizontal line for 'want' over here and 'need' over here. So far, this makes perfect sense but the subjective decision that every parent has to make in every single category is how much they're willing to pay for on the want/need continuum. The line we always try to use in our house is something that we refer to as the 'Lands End' line (my wife doesn’t totally agree with this). For us, ‘Lands End' stands for a quality product that's not a luxury product and what we're willing to pay for. This is your Lands End here in the rain boots category, but the Timberland boots? Probably more like over here. Hunter boots? Way over here. And then down here you've got Target and whatever.

What parents can do is that they can draw their version of the Lands End line and they can say, 'okay, you want something that's to the right of the Lands End line? You are going to have to pay for the difference between the $40 that we'd pay for the LL Bean or Lands End boots and the $60 that it'll cost for the Timberland boots or the $100 that it'll cost for the Hunter boots. This is your responsibility.

The additional twenty bucks or the sixty bucks, comes out of your allowance or savings.

How often do we have this conversation?

You have to have this version of the conversation for every item of clothing.

Eventually, if you establish a Lands End line for all clothing, then your kids always know the deal and so the baseline assumption is that you're going to buy them everything they need. And twice a year, they're going to need new things because they grow or their needs change, but eventually once they're eight or ten and they can start looking these things up themselves, and they're going to know where the Lands End line and look it up online.

LLB = LLBean

LE = "The Land's End line," where the kid has to pay for everything to the right of it

T = Timberland

H = Hunter Boots

On the bottom are the prices $40, $60 and $100 – with the kid having to make up a $20 difference or a $60 one.

I make no judgments about where you draw the line. Some people draw it at Patagonia, for instance – pricey but, arguably, better standards when it comes to environmental issues. Others buy at Target or second hand and give more to charity. The important thing is to articulate to kids where your line is and why so they can begin to understand how you make financial decisions.

How do parents comfort a child who feels badly for not being able to have those things?

They can have them. They just have to pay for them. So, they've to decide what's important.

But they're only making small allowance, one presumes. It'll take a long time to save up $60. What do parents say?

They say, 'you're going to be able to get there 30% of the time.' To me, that's sort of a reasonable goal. You want to give them just enough allowance so that they can get some of the things that they want but not so much that they don't have to make a lot of hard choices.

Aren't they all hard choices?

We're in the adult making business here, and adults have to make tradeoffs. If the point here is to use money as a teaching tool, then they need to be making their own tradeoffs at the earliest possible moment.

What public opinion do you want to change?

I would like to change the public opinion that all rich kids are spoiled and that diversity education begins and ends with discussions about race. Race is important, but it's just one part of the diversity.

What do you think caused this current trajectory that everything concerning diversity is about race?

Just about all private schools now have a director of diversity, sometimes more than one person working on diversity programming and have a thorough curriculum dealing with racial issues, which is great. But many of these programs don't have very much to say about social class. One of the reasons why? It’s difficult to talk about social class in a community where you need to hand over twenty or thirty or forty thousand dollars to walk in the door each year.

Why is it so hard for us to have these conversations?

I can tell you why it's easier to avoid. One of the reasons it's easier to avoid is that you can usually, not always, but usually tell that somebody is a different race by looking at them. With social class, it isn't always clear at first glance. It makes it easier for us to avoid talking about the difference even though to somebody who is different from a social class perspective – particularly in a private school context – that difference may be as impactful as a racial difference would be.

If you're someone who has less, in any community, it's not always easy to know who the people are who are like you.

I also think the bigger reason why it's important in private school is because it's just a radically uncomfortable thing to talk about in a community where not everybody can come. Not everybody's accepted and not everybody's rich enough to pay and there isn't enough financial aid available to make the schools reflective of their larger communities – ever.

Is there a mission to your book?

The mission is that we are going to be better at money than our parents were. We're going to be better at talking about money than our parents were. We're going to end what I think is an epidemic of silence around money in families where it's presumed to be an off limits, age inappropriate, impolite, impolitic topic of conversation with children.

What result are you looking for?

The result is that more and more kids will increasingly WIN their twenties financially. We will see a reversal of the trend where kids get themselves into a really bad student loan debt, or credit card debt because they've been trained as kids to think about wants and needs and the difference between the two and how to manage their own emotions as much as they're managing their own finances. I hope it all works out that way.

Do you think they'll share more and give back as a generation?

I hope that kids will be more conscious as they become adults of how good it feels to give. There's a whole chapter in the book about how to think about giving and how to talk about giving.

Secret source?

A secret that was being kept from me for the last twenty years is that people with a history of back problems can actually run and run far. I've taken up half marathons in the last couple years after two decades of pretty awful back problems and I've been totally fine. In fact, I haven't had a severe back episode since I took up the running. I don't know if one has something to do with the other but most people will tell you that you shouldn't go out pounding the pavement if you've got a history of back problems and disc problems.

Where do you run?

In Prospect Park in Brooklyn. It’s also the best way to explore a city or reintroduce yourself to a city that you thought you knew. It's now my favorite thing to go out running wherever I am.

Where do you get your news?

I get my news from the New York Times – both online and print. I flip through the paper in the morning. I read on the phone while on the subway, and I read on tablet when on vacation. At the office, I read the New York Times on the desktop computer.

Where do I pick up the best tips and story ideas? I'd say Twitter, but also Facebook. Facebook's news algorithm continues to get better and better. Twitter is like my own self-assembled wire service and I'm guaranteed to get things I'm looking for.